Canine Parvovirus: Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention

Canine Parvovirus (or “Parvo” as it is commonly referred to) is highly contagious virus infection that is spread from dog to dog by direct or indirect contact with their feces.

Canine Parvovirus affects domestic dogs and also other canine species including foxes, wolves, and coyotes.

The disease is primarily spread through fecal matter in dirt. It can also live on surfaces and objects such as shoes, clothing, food and water dishes, toys, bedding and towels.

The virus can survive in the ground for years and is often found in yards and dog parks where pets that have had the illness carry it.

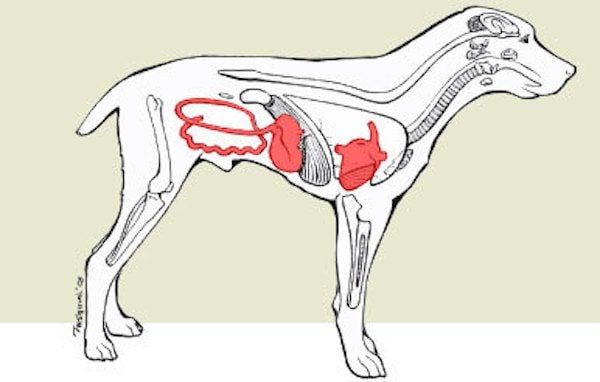

Dog Affected by Parvovirus

Parvovirus can be shed in the feces of a dog 3 to 4 days after infection, but before clinical signs of illness appear in a dog. At this stage, infected animals shed huge amounts of the virus. Dogs that have recovered from parvo can also still transmit the disease up to 3 weeks (or sometimes even up to 6 weeks) after recovery.

The virus is extremely hardy and survives through very cold and hot temperatures. Occasionally, outbreaks will occur in shelters when a stray dog that is infected is taken in, or in unhygienic kennels (e.g. puppy mills) where dogs usually are unvaccinated. But any unvaccinated dog can catch parvovirus. That is why the virus is particularly dangerous to dogs under a year old that have not been vaccinated, or only received part of their course of injections.

Certain breeds, such as Rottweilers, Doberman Pinschers, and Pitbull terriers, as well as other black and tan colored dogs, may be more susceptible to parvovirus.

Dogs that are treated early and aggressively usually pull through, with mortality rates for the disease being between 5% and 20%. However, chances of survival for puppies are much lower than older dogs. Even when dogs given veterinarian care, there is no guarantee of survival.

The virus kills through a combination of attacks. Dogs who catch parvovirus usually die from the dehydration it causes, or from secondary infections, rather than the virus itself.

Diarrhea and vomiting leads to extreme fluid loss and dehydration that in turn, leads to shock and death. Loss of the intestinal barrier allows bacterial invasion of potentially the entire body and septic shock result.

Concurrent infections often occur because of multiple factors such as age, breed, stress, and the overall general health of the dog. Bacteria, parasites and canine coronavirus all increase the risk of a dog getting a severe infection, which complicates treatment of the disease. Also, red and white blood cell levels drop dangerously low resulting in anemia and loss of immunity.

In cases of the more uncommon cardiovascular form of parvovirus, the heart muscle is attacked leading to death.

Dogs with severe parvovirus infections can die within 48 to 72 hours of evincing symptoms if they are not treated with fluids and antibiotics.

Types and Forms of Parvovirus

Canine Parvovirus is a relatively new disease. The CPV1 strain was detected in the late 1960s. Then a new strain, CPV2 was detected in the late 1970s.

CPV2 is more virulent strain and affects more dogs than the original and has several mutated strains – CPV2a and CPV2b – which are believed to cause most cases of canine parvovirus infection nowadays.

A third type, CPV2c, has been recently discovered in Italy, Spain and Vietnam and is spreading to other countries as well.

Canine Parvovirus has two forms – an intestinal form and a cardiac form. Depending on the form of parvovirus a dog contracts, symptoms and outcomes of the disease can vary.

Intestinal Form

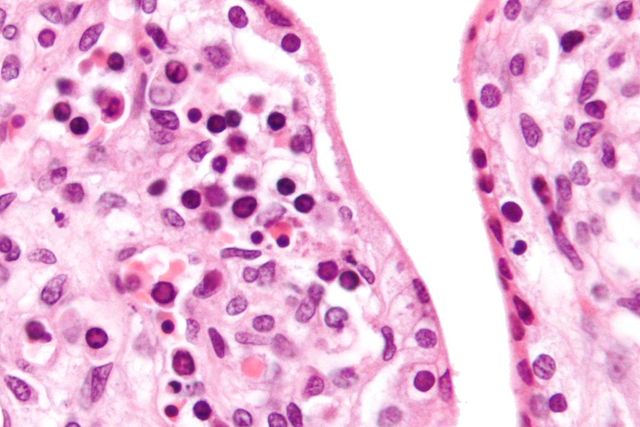

The intestinal form is the most common form of canine parvovirus. A dog’s intestinal lining is affected and blood, protein and bacteria leak into the intestines leading to anemia (lack of red blood cells that provide oxygen to the body) and endotoxemia (which leads to septic shock).

Affected dogs have a distinctive odor in the later stages of the infection. At later stages, white blood cell counts fall as well further weakening the dog. Any or all of these factors can lead to shock and death.

Cardiac Form

The cardiac form of parvovirus is much rarer. It is more commonly seen in puppies where mothers may not have been vaccinated against the disease and infects her pups in utero or shortly after birth until 8 weeks of age. The virus attacks the heart muscle. A puppy often dies suddenly without any sign or after a brief period of breathing difficulty.

This form of the disease may or may not be accompanied with the signs and symptoms of the intestinal form. However, this form is now rarely seen due to widespread vaccination of breeding dogs. That said, there are higher instances in puppies that come from puppy mills or stray dogs.

Symptoms of Parvovirus

There is typically an incubation period of 3 to 7 days between initial infection and onset of first symptoms. Usually the lymph nodes in the throat are where the virus incubates for a few days, after which the virus enters the bloodstream and into the organs. The two areas typically hit hardest by CPV are the bone marrow and intestinal walls.

Three to four days following infection, the virus is shed in the feces for up to three weeks, and the dog may remain an asymptomatic carrier and shed the virus periodically.

The virus is usually more deadly if the dog is concurrently infested with worms or other intestinal parasites.

Common signs of the intestinal form are severe vomiting and diarrhea. Symptoms include:

- Lethargy (lack of energy)

- Severe and/or bloody diarrhea

- Vomiting

- Fever

- Loss of appetite

- Dehydration

- Seizures

The cardiac form of parvo causes respiratory and cardiovascular failure. There are several tests that can be run by your veterinarian to help determine whether what is affecting your dog is CPV or some other problem.

Diagnosis of Parvovirus

By far the most common and most convenient method of testing for the presence of CPV virus is the fecal ELISA test. ELISA is an acronym for enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay. A veterinarian can complete the test in less than 15 minutes. A small stool sample is necessary for the completion of the ELISA test. Though the ELISA test is quite accurate, there are some cases in which a false positive or false negative result may be obtained. In this case, further measures may have to be taken to establish a diagnosis of CPV.

If further testing is done, a white blood cell count test will usually definitively diagnose CPV. Because one of the first things the parvovirus infects is the bone marrow, a low white blood cell count can be indicative of CPV infection.

If the ELISA test was positive, but the dog has a normal white blood cell count, it is unlikely the animal is infected with CPV. If however the dog has both a positive ELISA reading and a low white cell count, a fairly confident diagnosis of CPV may be made. PCR has also become available to diagnose CPV2, and can be used later in the disease when potentially less virus is being shed in the feces that may not be detectable by ELISA test.

Clinically, the intestinal form of the infection can sometimes be confused with coronavirus or other forms of enteritis. Parvovirus, however, is more serious and the presence of bloody diarrhea, a low white blood cell count, and necrosis of the intestinal lining also point more towards parvovirus, especially in an unvaccinated dog. The cardiac form is typically easier to diagnose because the symptoms are quite distinct.

Treatment of Parvovirus

Vet hospitalization is required to treat parvovirus, where supportive care is administered. Treatments may vary between individuals, but certain aspects are considered vital for all patients.

This includes:

- Administering intravenous fluids and nutrients to help the dog combat the severe dehydration and electrolyte imbalances that result from vomiting and diarrhea.

- Antibiotics administered either through IV drip or injection to counteract the secondary bacterial infections that result.

- Medications to control nausea and vomiting are sometimes added to the IV fluid bag.

Overall, care of dogs with CPV centers around fluid replacement and constant monitoring of bodily functions. As many dogs with severe forms also have intestinal or worms, de-worming medication may also be administered.

In some cases a blood plasma transfusion is given if extreme protein loss, anemia or drastic low white blood cell levels occur. Experimental treatments include giving blood plasma transfusion from a donor dog that has already survived CPV is sometimes used to provide passive immunity to the sick dog. However there is no controlled studies regarding this treatment.

Once the dog can keep fluids down, the IV fluids are gradually discontinued, and very bland food slowly introduced. A puppy with minimal symptoms can recover in 2 or 3 days if the IV fluids are begun as soon as symptoms are noticed and the CPV test confirms the diagnosis.

If more severe, depending on treatment, puppies can remain ill from 5 days up to 2 weeks. However, even with hospitalization, there is no guarantee that the dog will be cured and survive. That said, puppies that survive for 3 to 4 days generally have a good chance of making a full recovery within a week.

A dog that successfully recovers from CPV2 generally remains contagious for up to 3 weeks, but it is possible they may remain contagious for up to 6 weeks. Therefore infected dogs should be quarantined and have no, or limited exposure to other dogs until the risk has past.

Neighbors and family members with dogs should be notified of infected animals so that they can ensure that their dogs are vaccinated or tested for immunity.

Prevention of Parvovirus

Treating parvo can be quite costly (running thousands of dollars) so having a puppy and dog vaccinated to prevent parvovirus infection is the only effective prevention. Puppies too young to receive vaccinations, or only partially through their vaccination regime, should have limited exposure to outdoor areas such as dog parks to prevent exposure to viruses such as parvo.

Veterinarians often recommend this for all puppies until their vaccination series in completed at age 16 weeks. It’s a delicate balance between socializing your puppy and giving your puppy time to have defenses against disease.

Veterinarians usually administer the CPV vaccine as part of a combination shot which includes, among others, the distemper and coronavirus vaccines. These shots are given every 3 to 4 weeks from the time a puppy is 6 weeks old until he is at least 16 weeks of age.

Manufacturers of the vaccine include: Pfizer’s Vanguard PLUS 5 Vaccine, Intervet’s Progard-6 Vaccine, Schering-Plough Animal Health’s Galaxy Vaccine and Fort Dodge’s Duramune Puppy Shot among possible others.

The duration of immunity of vaccines for CPV2 has been tested for all major vaccine manufacturers in the United States and has been found to be at least 3 years after the initial puppy series and a booster 1 year later. The vaccine will take up to 2 weeks to reach effective levels of immunity.

The reason that vaccination is the primary tool for prevention is that the parvovirus is extremely difficult to eradicate. It is resistant to every household cleaning product, with the exception of bleach.

It can live in the soil, grass, lawns, and homes through extreme heat and cold. It will survive in the soil for over a year. It can be carried around on shoes, clothes, bags, fur and other surfaces.

As the virus can also live on surfaces such as food and water bowls, crates, bedding and towels be cautious if you receive or purchase second hand materials for your dog. Be sure to thoroughly bleach the items to decontaminate them.

As many of these environments are not decontaminated with bleach regularly, it is safe to assume most areas carry some level of contamination.

Dogs that have recovered from parvovirus should remain quarantined for at least three weeks and have no, or limited exposure, to other dogs until the risk has past. Dogs that visit regularly with an infected dog such as those of neighbors and friends should be vaccinated or tested for immunity to avoid getting infected.

Since the introduction of effective vaccinations, parvovirus has become much less of a threat to domesticated dogs. That said, parvovirus is a serious illness if contracted, so taking the necessary step towards prevention is key to avoiding putting your dog at risk.