How to Protect Dogs from Lungworm / French Heartworm

French Heartworm, or Lungworm, as it is commonly referred to in the United Kingdom, is caused by a parasitic nematode (roundworm or lungworm), Angiostrongylus vasorum. The roundworm infects dogs and other canine species, such as foxes and wolves, and causes canine angiostrongylosis.

Dogs of all ages and breeds can become infected with French Heartworm / Lungworm. However, younger dogs seem to be more prone to picking up the parasite. Finding Angiostrongylus vasorum in a dog should always be treated as soon as possible, as it is an extremely dangerous disease. Left untreated, the infection can be fatal to dogs. However if diagnosed early, it can be treated successfully.

The lungworm parasite is carried by slugs and snails and infects a dog directly through contact. Dogs can become infected when they eat these common garden pests or come in contact with the slime trails these creatures leave in puddles, on grass, on the ground and on objects, such as outdoor water bowls and toys exposed to the outdoors.

Dogs cannot infect each other directly, as the parasite is only infective after first developing inside a slug or snail. The disease is also not transmitted to humans. Despite its common names, this particular disease should not be confused with Heartworm (caused by Dirofilaria Immitis) or Rat Lungworm (caused by another roundworm, Angiostrongylus cantonensis, which can infect humans and dogs). To learn more on Heartworm, read our article: How one mosquito bite can kill your dog.

Areas affected by French Heartworm / Lungworm

Angiostrongylus vasorum’s native area is Western Europe, and is most common in France, United Kingdom, Ireland and Spain). Traditional hotspots include South Wales and South West England. However, in the past few years the parasite has spread to other parts of Britain and is putting more dogs at risk. In south east England, 23% of the fox population is infected. There also appears to be a correlation between high fox incidence and domestic dog incidence. This is most likely because snails and slugs come in contact with an infected fox feces and then spread it to dogs in the same territory.

The parasite has also been found in other countries in Europe such as Denmark, Germany, Greece, Italy, France, Sweden and Switzerland. In North America, Newfoundland in Eastern Canada is the one area with reported cases.

The disease is still relatively rare, although it is considered an emerging canine disease.

Lifecycle

Adult lungworms live in the right side of the heart and great pulmonary vessels of a dog. Eggs are laid and move through a dog’s blood stream to the lungs, where they hatch larvae, which are coughed up and swallowed. They are then passed in the dog’s feces and eaten by slugs and snails (intermediate hosts), where they undergo further development. Dogs, foxes, wolves and frogs (paratenic host) then eat the slugs or snails. The larvae are absorbed from the gut into the blood stream where they end up in the heart again. The whole lifecycle takes about 1 to 2 months in total.

The video below explains Angiostrongylus vasorum’s life cycle in further detail.

Symptoms

Lungworm infections can result in a number of general symptoms, which may easily be confused with other illnesses, but typically evince in cardio-respiratory (heart and lung) problems first. Symptoms can start to show as late as a month or two after infection (in keeping with the parasite’s life cycle).

As blood vessels become blocked by the worms, a dog will start to cough and tire easily. It is important to note that some dogs do not initially show any outward signs of lungworm infection.

When the parasitic worms begin to take over, a dog’s immune system gradually weakens and neurological issues may begin to present. If left untreated, the dog will eventually die.

Symptoms of lungworm include:

- breathing problems – coughing, rapid heavy breathing, tiring easily, collapse, exercise intolerance.

- general sickness – weight loss, loss of appetite, vomiting, diarrhoea.

- poor blood clotting (coagulopathy) – blood unable to clot, anemia, pale mucous membranes, bleeding in the eye, excessive bruising (haematomas), nose bleeds, excessive bleeding from small wounds.

- neurological – behavioral changes (such as depression), paralysis, seizures, spine pain, lack of coordination (ataxia), loss of vision.

Diagnosis

Veterinarians will need to run several types of tests to determine if a dog has lungworms. Detecting Angiostrongylus vasorum can be difficult as the tests are not always 100% reliable and may have to be done more than once. This is because lungworms shed larvae intermittently, and therefore the larvae are not always present in fecal or blood samples. Therefore, several samples over a period of time, may be necessary to get a positive diagnosis.

Two tests are available and both appear to have similar detection rate:

- Test of the feces, using what is called a fecal Baermanan test.

- Test of the blood, using a real-time blood PCR test, which detects the parasite’s DNA.

If a bronchoscopy (looking into the airways with a microscopic camera system) is performed blood may be seen due to the damage being done by the lungworm infection.

Another sign of infection is endocarditis (inflammation) of the right side of the heart and the tricuspid valve.

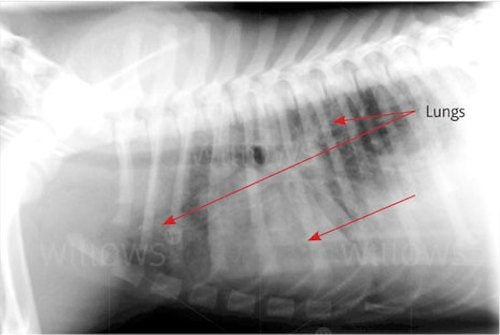

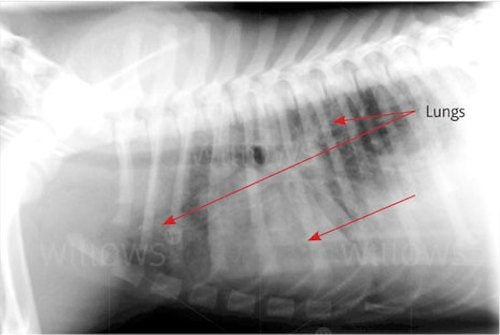

An X-ray image will show lung lesions (mottled lungs) if the adult lungworms have infected a dog’s heart and lungs.

Treatment

French Heartworm/Lungworm is treatable. If treated, full recovery is most likely in mild and moderate cases. Cases with severe dyspnoea (shortness of breath), bleeding and neurological symptoms, are more challenging and therefore will have a guarded prognosis and will depend on the individual dog. In severe cases, mild chronic respiratory disease may remain.

French Heartworm/Lungworm is treatable through anthelmintic drugs (drugs used to expel worms). Four drugs – fenbendazole, febantel, ivermectin and milbemycin – have been used successfully.

In the UK, two drugs are licensed for the treatment of A. vasorum:

- Moxidectin (brand name Advocate made by Bayer Animal Health)

- Milbemycin oxime (brand name Milbemax made by Novartis Animal Health)

One drug is also prescribed, but off license:

- Fenbendazole (brand name Panacur made by Intervet-Schering Plough Animal Health)

Supportive treatment is also recommended, depending on a dog’s clinical signs. These can include: anti-inflammatory corticosteroids, bronchodilators, cage rest, oxygen supplementation and blood products.

Some dogs suffer complications after treatment (fluid build-up and severe breathing difficulties), in which case antibiotics may then be necessary to treat any secondary respiratory infections.

A dog diagnosed with angiostrongylosis is at risk of re-infection, and should be protected with regular anthelmintic treatment every 3 months, or with a monthly spot-on preventative. Where possible, a dog’s exposure to snails and slugs should also be limited. Other dogs in the household should also be monitored and preventative treatment for them is also advised.

Prevention

Spring and autumn are the peak times for slug and snail activity because of the warm and damp weather conditions and therefore, are the highest risk times for lungworm infection.

Monthly-spot on preventative, such as Advocate, are available which target lungworms and other parasitic worms and parasites. A de-wormer is also available and is administered every three months.

Unless you live in an area where the lungworm is epidemic, preventatives are likely not necessary, and then, usually only necessary for the part of the year when slugs and snails are in “full force”.

Treatment for worms should be considered on an individual basis and in consultation with a veterinarian. If a dog likes to eat snails and slugs, he/she may need additional worming and monitoring.

If you live in an area that has had French Heartworm/Lungworm, here are a few tips to help reduce the risks to your dog:

- Keep your yard clear of dog feces as snails and slugs are attracted to it as a food source.

- Do not leave a dog’s toys or water bowls outside and clean them regularly.

- Cut long grass to discourage snails and slugs from living in it and to reduce chance your dog may eat it.

- Treat your yard with non-harmful (to your pet) pest control. (Slug and snail baits are very poisonous to your dog and not highly effective. Try non-toxic methods instead).

- Discourage your dog from sniffing and/or eating slugs or snails or slime trails.

- Discourage your dog from drinking from puddles and ponds.

- Discourage your dog from eating long grass during peak mollusc seasons.

Some suggested natural (non-pesticide) slug/snail traps are:

- Beer trap: mix a little flour with a stale beer and fill a shallow container with the rim 1 or 2 cm above the ground so that slugs and snails can climb. Substitute beer for wine, sugar water or water mixed with yeast.

- Coffee spray: make a weak coffee brew with ground coffee and water. Spray the plants.

- Pot trap: place a plant pot upside down in a shaded area of the garden away from seedlings and check regularly

- Hedgehogs: if you have the wild animals in your garden, encourage them to stay as they are natural predators of slugs and snails.

- Physical barriers: scatter crushed egg shells, sawdust or wood shavings around plants at risk.

If there has been an outbreak of French Heartworm/Lungworm in your neighborhood, be sure to alert the health authorities and other dog owners.