Valley Fever in Dogs: Symptoms, Treatment and Prevention

Dogs that become afflicted with Valley Fever face an array of health problems that can persist for years or an entire lifetime. That’s why identifying the symptoms and getting treatment as early as possible is very important.

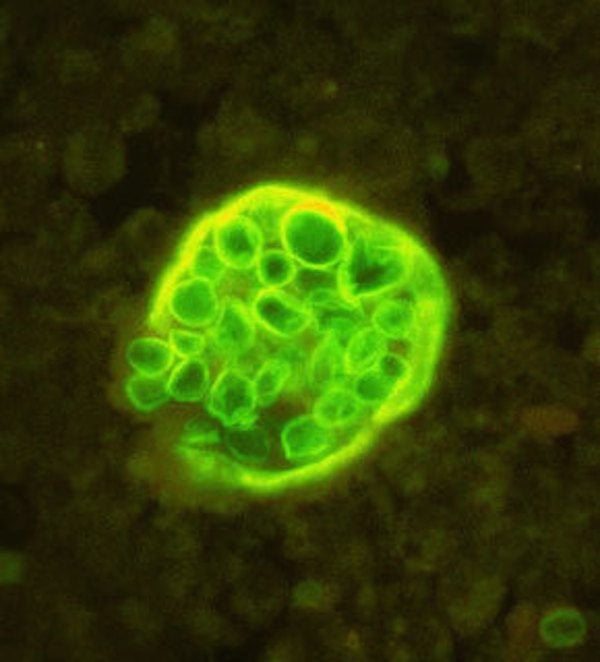

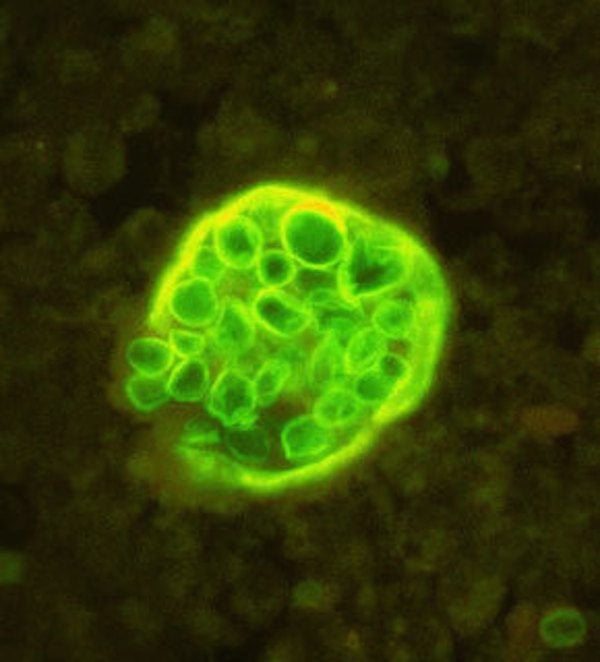

Coccidioidomycosis, otherwise known as Valley Fever (and sometimes referred to as “California disease” or “Desert rheumatism”), is an infectious disease caused by a fungal organism called Coccidioides Immitis. This fungus is located in the soil of certain regions of the southwestern United States and northern Mexico.

Dogs primarily contract Valley Fever in the low desert regions of Arizona, New Mexico and southwestern Texas and the central deserts of California.

Arizona sees 80% of all Valley Fever cases in humans, with most of those cases falling within the Phoenix-Tucson corridor, and 60% of Arizona’s Valley Fever cases occur in Maricopa County. In Arizona, the highest prevalence of infections occurs during June and July and from October through November.

The fungi’s spores are commonly found in the dirt in specific regions, and when that dirt is disturbed, the spores are released into the air. From there humans and animals inhale the fungal spores into their lungs.

Once inhaled, a human or dog can contract Valley Fever, although not all humans and animals that inhale the spores will end up developing Valley Fever. Dogs with weakened or compromised immune systems (as in humans) are more likely to contract Valley Fever.

Dogs are very susceptible to infections with Valley Fever because they sniff the ground and dig in the dirt, which means they have a larger chance of inhaling large numbers of spores at a time.

Dogs who spent more time outside, live on acreage, or walk in the desert regularly usually have higher incidences of Valley Fever.

The University of Arizona Valley Fever Center for Excellence estimates that dogs in Arizona have a 28% chance of catching Valley Fever by the age of two. Of these dogs, 6% will show signs of clinical illness within two years.

The disease is not contagious and many dogs contracting it will recover in a few weeks without the need of medical treatment. The infection starts in the lungs and usually affects the respiratory system. When it affects other parts of the body, it is called disseminated Valley Fever and can cause serious, life-threatening complications.

Diagnosis

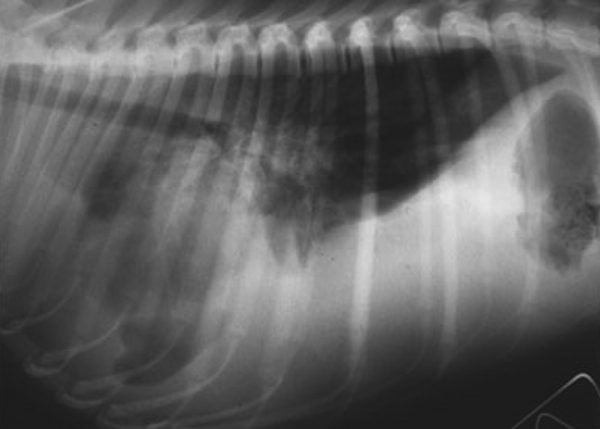

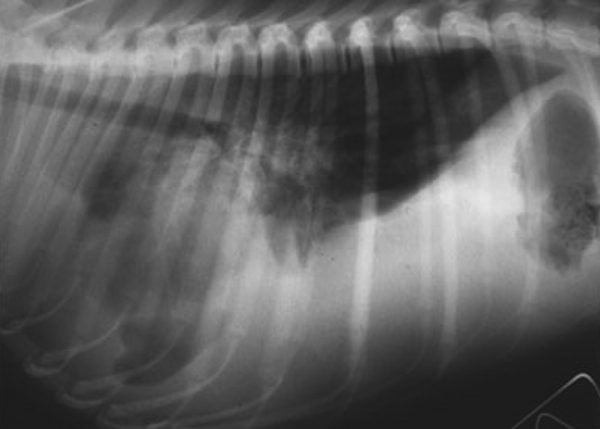

Diagnosis is made with a series of blood tests and x-rays. Radiographs (x-rays) will often show inflammation and enlarged lymph nodes on chest films but definitive diagnosis still requires a blood test. A Valley Fever test or Cocci test checks a dog’s blood to see if the animal is making antibodies against the fungus.

If the test is positive, it means your dog has been exposed to the fungus and a Cocci titer is then done. A titer is a measure of the patient’s immune response (antibodies) to the infectious organism. The higher the titer means a more severe case of the disease.

However, some very sick animals have low titers, or even negative tests. That is why x-rays, tissue biopsies or other tests may be required for a definitive diagnosis of Valley Fever/Coccidioidomycosis.

Symptoms

Symptoms vary but can include: loss of appetite, cough, difficulty breathing, Some dogs will not show any specific sign of infection, but pet owners will notice that their dog is lethargic and often have a decreased appetite. Other dogs may have cold- or flu-like symptoms or symptoms of pneumonia. If symptoms occur, they typically start 5 to 21 days after exposure to the fungus.

As the disease progresses other symptoms may evince that affect the neurological or skeletal-musculature functions such as: limping, inner eye infections (uveitis), skin lesions (red wounds, lumps), fever and seizures.

If your dog shows symptoms of Valley Fever he/she should be taken to the vet for testing to determine the severity of fungal infection and to determine what treatment may be necessary.

Treatment

Treatment most often depends on how severe the Valley Fever is and how far the infection has progressed and spread. In many cases, treatment will be required for 6 to 12 months.

The vet may choose to administer an antifungal treatment (azoles). With adequate antifungal therapy most dogs recover from the disease. Dogs with infection only in the lungs have the best prognosis for recovery and usually respond the quickest to treatment when the disease is treated early.

Dogs diagnosed with disseminated infection (where the infection has spread to other parts of the body), treatment is more complicated and outcomes more varied.

As with lung infections of Valley Fever, it seems that the majority of dogs with disseminated infection in the lung area respond well to medication and lead normal lives, but they often require drug treatment for a longer period of a year or more (12-18 months). In rare cases the dogs must be on the medication for life.

Dogs that have extensive lung disease may require hospitalization, or surgery to remove diseased lung, or they may die. If Valley Fever has spread to the brain, complications may arise. Dogs that respond to the medication sees about 80% recovery, but treatment may be required for life.

In animals with severe bone infections and the joint and swelling pain that goes with them, pain medication and anti-inflammatories will also be prescribed.

Relapses of Valley Fever can occur and although the frequency in dogs is not known, it is not uncommon. Relapses particularly occur in cases of disseminated Valley Fever, no matter how well the initial infection was treated.

In the case of a relapse, a return to medication is usually enough to make symptoms subside, but the dog may require several additional months of treatment. Dogs that experience more than one relapse or get very sick with the relapse should probably have lifetime treatment with medication considered.

Medications and Side Effects

Oral antifungal medication is prescribed in the form of twice daily pills or capsules. There are three common medications used to treat Valley Fever in dogs.

- Ketoconazole (generic or Nizoral brand)

- Fluconazole (generic or Diflucan brand)

- Itraconazole (Sporanox)

All “azoles” (ketoconazole, itraconazole, and fluconazole) can elevate the dog’s liver enzymes with continued use, so the dog’s liver values should be tested routinely on the advise of a veterinarian.

All the oral Valley Fever drugs cause birth defects in fetuses and should be avoided in pregnant animals unless the benefit to the mother outweighs any risk to the fetuses.

Common side effects include loss of appetite, nausea, vomiting and diarrhea.

Ketoconazole, available in generic form or as Nizoral, tends to be the least expensive of the group and is widely used, but has the highest incidence of side effects. It is often administered with Vitamin C to aid in absorption of the medicine. Common side effects include stomach and intestinal upset (more than with fluconazole), reversible lightening of the coat color, temporary sterility in male dogs.

Fluconazole, available in generic form or as Diflucan, is able to cross into the central nervous system and is the only drug used to treat “central” valley fever infection (typically the seizuring pet), as it will cross into the brain and eye tissues.

Fluconazole seems to have fewer side effects than Ketoconazole. It has excellent absorption, even in dogs not eating and is generally easier on the animal’s liver. Side effects are that it can affect the dog’s kidneys, temporary dandruff and occasionally excessive thirst and urination.

Itraconazole, available as Sporanox has been shown to be a more potent drug against Valley Fever than fluconazole in laboratory studies, but has some drawbacks when used clinically. Itraconazole is often effective in cases where dogs are not responding well on fluconazole.

Side effects include stomach and intestinal upset, increase in liver enzymes and skin reactions including abscesses. When it causes ulcerated lesions a dog may need to be treated by a different medication. It is also less absorbed from the GI tract than fluconazole. Currently the drug is available in generic capsule form for humans. There is also a liquid form of Sporanox which can be good for small dogs.

Regardless of the drug used it is important to monitor the appetite and reaction of the drug with your dog and advise your veterinarian if any side effects are noted.

Other drugs under development include a new Valley Fever drug, nikkomycin Z, in dogs with Valley Fever pneumonia.

A vaccine is also under development. It is possible a vaccine will be available in the future to prevent Valley Fever or make it only a very mild illness in dogs.

Prevention

Unfortunately, there is not a vaccine to prevent this disease. Reassuringly it is important to recognize that many dogs will never become ill from the fungus. The best pet owners can do is to be aware of symptoms and respond quickly to signs of the disease in their dog.

As the fungus is found in outdoor areas, obviously dogs that spend a lot of time outdoors are more likely to inhale the spores than dogs that spend a lot of time indoors.

Things you can do to reduce the likelihood of your dog’s exposure to the fungus are:

- avoid activities that generate dust

- reduce digging behavior by dogs

- prevent sniffing in rodent holes

- keep dogs indoors more than outdoors

- be aware of areas that have outbreaks

Environments and weather conditions that tend disseminate the fungus are:

- Hiking/ hunting areas such as in the native desert environment

- Dust storms

- New construction developments

- Recent pool digs or landscaping

- Wet weather followed by hot weather

Treating the soil will not work as the fungus lives in spotty areas and can live up to 12 inches deep in the ground. However, yard ground cover such as grass or deep gravel that reduces dust is helpful.

Unfortunately, with weather patters in the southwestern United States changing to include hotter temperatures and more intense dust storms, Valley Fever will continue to grow in presence.